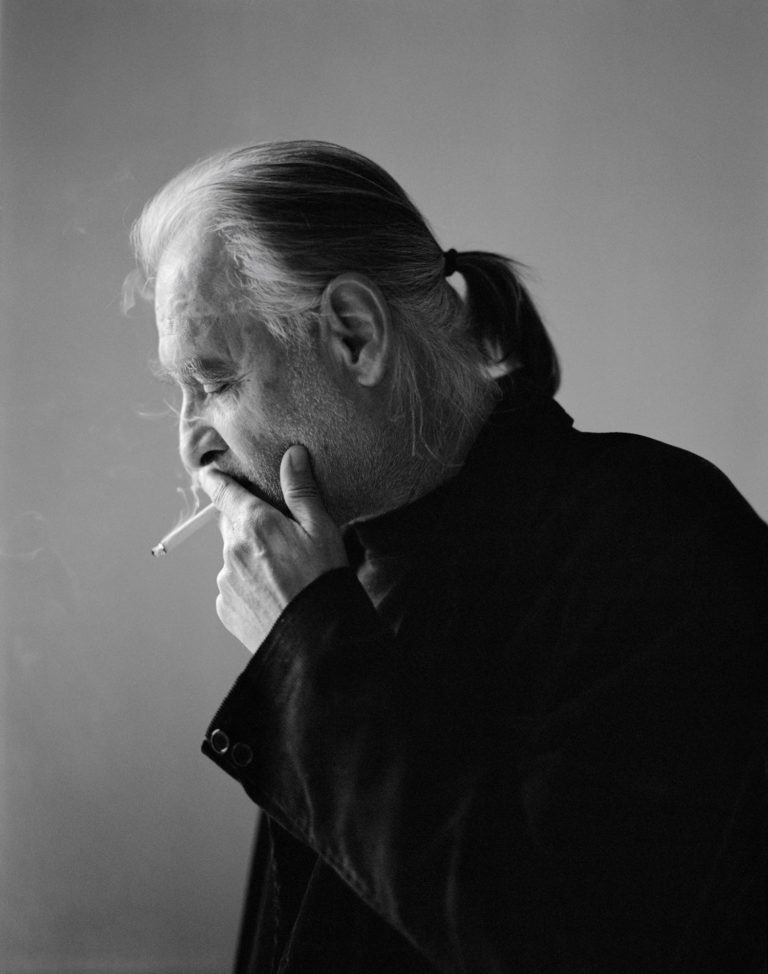

Silk Road Film Festival 2017 Honours Special Lifetime Achievement Award to Béla Tarr

Béla Tarr is widely considered as one of the most important film directors of the past thirty years. While aspects of his cinema make it difficult for him to attract a mainstream audience, it is really among directors, film critics, academics, aspiring students and viewers of cinema as an art form that Tarr’s work finds its real appreciation. His influence over the past thirty years cannot be overstated. His contribution as one of the last European “auteurs” continues to be a source of inspiration to young film-makers around the world. However, the importance of Béla Tarr’s films in the 1990s are not only limited to their stylistic and aesthetic values. According to his biographer Novacs “they offer the most powerful and complex vision of the historical situation in the Eastern European region in that decade.”

Béla Tarr, Dean of the Film Factory at the Sarajevo Film Academy which provides a doctoral program that Tarr founded in Sarajevo and is composed of theoretical lectures and directing workshops. It provides funding to many young film-makers to undertake a Ph.D in cinema. In the past Tarr has been also a frequent visiting professor of the Berlin film school where he would spend a couple of months each year. In addition, he has held many temporary positions at film academies around the world such as the Dean of the Asian Film Academy in 2014.

However, Tarr’s most significant contribution to academia is the importance of his art itself and the research that it has stimulated. A quick search of his name on TCD’s library page produces 1907 results of which 85 are books and 385 journal articles. His art is not only confined to film analysis, but transcends other disciplines such as politics, philosophy and literature. Articles explore his work through analyses of Nietzsche’s philosophy, as well as TCD’s own Samuel Beckett.

His work has received many awards. Most notable is a nomination for the Palme d’Or in 2007 for “A Man from London” as well as winning the Foreign Cineaste of the Year in 2005. He has won several awards at the Berlin Film festival for his films Sátántangó (1994) Werckmeister Harmonies (2001) and The Turin Horse (2011). He has also been awarded numerous awards for significant contribution to film around the world as well as receiving in 2004 the highest national award an artist can get in Hungary.

But it is arguably his influence on some of the most prominent movie-makers that show one of Tarr’s most outstanding contributions. Gus Van Sant, who doesn’t hide the influence of Tarr on his own in work, in particular his Palme d’Or success “Elephant”, writes in a piece for a MoMA Retrospection of Tarr’s work:

Béla’s works … find themselves contemplating life in a way that is almost impossible watching an ordinary modern film. They get so much closer to the real rhythms of life that it is like seeing the birth of a new cinema. He is one of the few genuinely visionary filmmakers.

Martin Scorsese names Tarr as “one of cinema’s most adventurous artists, and his films, like ‘Satantango’ and ‘The Turin Horse,’ are truly experiences that you absorb, and that keep developing in the mind”.

These comments point to the essence of Tarr’s cinema and the guiding thread that unifies all of his work: the preservation of human dignity. For Tarr filmmaking has always been a question of inner moral conviction and to fight for and preserve the dignity of those who are the least fortunate in society. In order then for his audience to truly contemplate human dignity, it is Tarr’s belief that cinema must reflect these hardships. If at times his scenes seem long, arduous and testing it is because it is so for his characters in that moment. Instead of using cinema as a way of escaping our human condition Tarr holds it up as a mirror, not to prescribe action with respect to political and social change but more importantly to pose the problem at the ontological and metaphysical level. In what may appear at times as a bleak pessimism, in which flawed individuals are pitted against the heaviness of their existence, Tarr creates a space in which human dignity takes centre stage. In contemplating the humanity and dignity of individuals, Tarr’s work follows a long tradition of the human spirit that calls for compassion in face of human suffering.

Silk Road Film Festival 2015 Honours Special Lifetime Achievement Award to Master Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro.

Vittorio Storaro, the award-winning cinematographer who won Oscars for “Apocalypse Now“, “Reds” and “The Last Emperor“. He was born on June 24, 1940 in Rome, where his father was a projectionist at the Lux Film Studio. At the age of 11, he began studying photography at a technical school. He enrolled at C.I.A.C (Italian Cinemagraphic Training Centre) and subsequently continued his education at the state cinematography school Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. When he enrolled at the school at the age of 18, he was one of its youngest students ever.

At the age of 20, Storaro was employed as an assistant cameraman and was promoted to camera operator within a year. Storaro spent several years visiting galleries and studying the works of great painters, writers, musicians and other artists. In 1966, he went back to work as an assistant cameraman on Before the Revolution, one of the first films directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. Storaro earned his first credit as a cinematographer in 1968 for “Giovinezza, giovinezza”. His third film was “The Spider’s Stratagem” which began his long collaboration with Bertolucci. He also shot “The Conformist“, “Last Tango in Paris“, “Luna“, “The Sheltering Sky (1990)_”, “Little Buddha,” for Bertolucci.

He won his first Oscar for the cinematography of “Apocalypse Now“, for which director Francis Ford Coppola gave him free rein to design the visual look of the picture. Storaro originally had been reluctant to take the assignment as he considered Gordon Willis to be Coppola’s cinematographer, but Coppola wanted him, possibly because of his having shot “Last Tango in Paris, which had starred Marlon Brando. Brando’s performance in the film had been semi-improvised, and Coppola has planned on a similar tack for his scenes in the jungle with Brando’s character Colonel Kurtz.

The results of their collaboration were masterful, and he later shot the 3-D short “Captain EO“, the feature films “One from the Heart” and “Tucker: The Man and His Dream,” and the “Life without Zoe” segment of “New York Stories” for Coppola. He won his second Oscar as the director of photography on Warren Beatty‘s “Reds” and subsequently shot “Dick Tracy” and “Bulworth” for Beatty He won his third Oscar as the director of photography on Bertolucci’s Best Picture Academy Award-winner “The Last Emperor“.

“All great films are a resolution of a conflict between darkness and light,” Storaro says. “There is no single right way to express yourself. There are infinite possibilities for the use of light with shadows and colors. The decisions you make about composition, movement and the countless combinations of these and other variables is what makes it an art.”

According to Storaro, “Some people will tell you that technology will make it easier for one person to make a movie alone but cinema is not an individual art.” Storaro disagrees. “It takes many people to make a movie. You can call them collaborators or co-authors. There is a common intelligence. The cinema never has the reality of a painting or a photograph because you make decisions about what the audience should see, hear and how it is presented to them. You make choices which super-impose your own interpretations of reality.”

Storaro believes that, “It is our obligation to defend the audiences’ rights to see the images and to hear the sounds the way we have expressed ourselves as artists,”.

During the 1970s, the metaphor of cinematography as ‘painting with light’ took hold. Storaro, however, adds motion to the mix. Cinematography, to the great D.P., is writing with light and motion, the literal translation of the word cinematography, which derives from Greek

“It describes the real meaning of what we are attempting to accomplish,” Storaro says. “We are writing stories with light and darkness, motion and colors. It is a language with its own vocabulary and unlimited possibilities for expressing our inner thoughts and feelings.”

As a cinematographer, he is highly innovative. He had Rosco International fabricate a series of custom color gels for his lighting, which he used to implement his theories about emotional response to color. The “Storaro Selection” of color gels is available for other cinematographers from Rosco.

He created the “Univision” film system, which is a 35mm format based on film stock with three perforation that provides an aspect ratio of 2:1, which Storaro feels is a good compromise between the 2.35:1 and 1.85:1 wide-screen ratios favored by most filmmakers. Storaro developed the new technology with the intention of 2:1 becoming the universal aspect ratio for both movies and television in the digital age. He first shot the television mini-series “Dune” with the Univision system.

Storaro is the youngest person to receive the American Society of Cinematographer’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and only the second recipient after Sven Nykvist not to be a U.S. citizen.

Silk Road Film Festival 2014 Honours Special Lifetime Achievement Award to Master Iranian Cinematographer.

Mahmoud Kalari was born on April 31, 1951 in Tehran, Iran. After completing photography courses in the United States, he held his first photo exhibition titled “Visit with People Around Us” at Tehran University in 1976. A few years later he became employed by Paris based Sigma Photo News Agency and worked for them for four years. In 1980 he was ranked one of the ’15 Best Photographers of the Year’ by Time Magazine, and his photos could be seen in French, German, and American magazines. Kalari moved back to Iran and from 1982 to 1984 worked as the supervisor of the Tehran National TV Photography Unit and taught photojournalism at Tehran University as a guest professor.

Kalari started his film career in 1984 as the cinematographer of Jadehay sard (1985) (Frosty Roads) for which he won the Best Cinematography award at Tehran’s Fajr International Film Festival. He has shot more than 65 films since then including some of the most critically acclaimed and talked about movies in Iran and internationally. To mention a few: The Lead (1988) (winner of the best cinematography), Reyhaneh (1995) (screened at San Sebastian and Montreal Film Festivals), A Time for Love (1990) (filmed in Turkey and screened at Cannes Film Festival), “From Karkheh to Rein” (1990) (filmed in Germany and screened at Hamburg and Mannheim Film Festivals), Sara(1993) (screened at San Sebastian, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago Film Festivals) Salaam Cinema (1995) (screened at Montreal, Toronto, Los Angeles, New York, and Cannes Film Festivals) Gabbeh (1996) (screened at Cannes, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, New York, Los Angeles and 21 other International Film Festivals around the world, winner of Best Cinematography at Fajr International Film Festival and winner of Fujifilm Motion Picture Award), Leila (1997) (screened at 7 international film festivals and the winner of the best cinematography at Fajr Film Festival), The Pear Tree (1998) (winner of Silver Hugo at Chicago Film Festival and chosen as the Best Motion Picture Photography by the international jury of the Fajr Film Festival), The Wind Will Carry Us(1999) for which Kalari received nominations for Best Cinematography in the Main Competition of Plus CAMEIMAGE International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography, and Offside (2006) (screened at Berlin, New York, and AFI Film Festivals).

Kalari directorial debut is The Cloud and the Rising Sun (1997) on which he was also the writer and cinematographer. It was screened at Montreal and Chicago Film Festivals and won the Best Film award at Argentina Mardel Plata Film Festival.

Kalari was selected as a Jury Panelist for Poland Film Festival both in 1999 and 2000. In 2001, Nant Festival in Paris held a tribute to his work as a photographer and exhibited his photographs. In 2005 he won the best cinematography award for Bab’Aziz – The Prince That Contemplated His Soul (2005), directed by Tunisian-French director Nacer Khemir, from the Tatarstan International Muslim Film Festival. Later, a gallery of his photos shot during the Iranian Revolution of 1979 was opened to the public, and a photo book of his work from that era was published. Kalari’s work on the internationally critically acclaimed and Oscar winner film, A Separation (2011), earned him a Silver Frog from Plus CAMEIMAGE International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography in 2011.

He has brought the vision of many great Iranian directors to life, such as Masud Kimiai, Ali Hatami, Dariush Mehrjui, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Tahmineh Milani, Palme d’Or winner Abbas Kiarostami, Oscar nominee Majid Majidi, and Oscar winner Asghar Farhadi. Kalari has had workshops in different cities of Iran and teaches cinematography as he continues to shoot.